This week’s blog post is taking us to Israel and to the Jewish diaspora again and we are going to look at the vocabulary related to the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashana ראש השנה, which was celebrated this week, and the foods that are usually eaten on this holiday (these vary depending on the country of origin).

Category Archives: cuisine

Focus on culture: Turkish coffee/Türk Kahvesi

Today’s blog post is taking us to Turkey (Türkiye) and to the tradition of Türk kahvesi or Turkish coffee, which is recognized as an Intangible Heritage of Turkey by UNESCO.

Türk kahvesi is a special method of coffee preparation (i.e. not a special kind of coffee bean) in which coffee is generally prepared unfiltered from roasted and finely ground coffee beans (kahve çekirdekleri; sing.kahve çekirdeği) which are simmered (but not boiled) in a cezve, a special Turkish coffee pot. The term cezve derives from the Arabic term جذوة ’ember’. The coffee is served in a cup, fincan, where the coffee grounds (kahve telvesi) are allowed to settle. If prepared well, the coffee has a thick layer of foam at the top (köpük). The word for ‘coffee’ kahve comes from the Arabic word قهوة qahwah. The importance of coffee in Turkish culture is also reflected in the word kahvaltı, breakfast, which literally means ‘before coffee’ (kahve + altı ‘under/before’.

To prepare Turkish coffee, finely ground coffee powder is immersed in hot, but not boiling, water. For each cup, 1 – 2 heaped teaspoons of coffee are used, which along with some sugar, are usually added to the water rather than first being placed into the coffeepot. The mixture is then heated until it starts to boil – at this point it is taken off the heat source. When prepared properly, a layer of foam called köpük forms on the surface of the coffee.

Author: Oliver Merkel, via Wikipedia Commons

Preparation of mocha coffee (Turkish Coffee). 1: Ground coffee, water, sugar, and heat source. 2, 3: heat the water till it starts bubbling. 4: add coffee. 5: continue heating and mixing. 6: heat until the mixture starts to rise, then take off the heat source to settle it down while mixing the upper part (repeated many times). This creates a foamy top. 7: pour and serve hot

Turkish culture distinguishes between four degrees of sweetness of the coffee, depending on the amount of sugar, şeker, that is added:

- sade (plain; i.e. no sugar added)

- az şekerli (little sugar; about half a level teaspoon of sugar)

- orta şekerli (medium sugar; about one level teaspoon)

- çok şekerli (a lot of sugar; 1.5 – 2 level teaspoons).

The coffee grounds left in the cup after finishing your fincan (cup) of Turkish coffee can be used for fortune-telling, called kahve falı or tasseomancy: the cup is turned over on the saucer to cool down and the patterns left by the coffee grounds, kahve telvesi, can then be interpreted to tell one’s fortune.

For more information:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_coffee

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cezve

Is there also a special beverage in your country or are there any special customs or superstitions associated with a beverage in your country? Tell us about it in the comments! 🙂

Focus on culture: Jól in Iceland

Today’s blog post will take us to Iceland and to some special Icelandic Jól (or Christmas) customs. Jól is based on the Old Norse religious festival called Yule.

Today’s blog post will take us to Iceland and to some special Icelandic Jól (or Christmas) customs. Jól is based on the Old Norse religious festival called Yule.

Jól is celebrated on 24 December, but the Jól season includes events over several weeks: Aðventa (advent, the four Sundays preceding jól), aðfangadagskvöld (Yule eve), jóladagur (Yule day), annar í jólum (Boxing day), gamlársdagur (old years day), nýársdagur (New Year’s Day) and þrettándinn (the thirteenth, and final day of the season).

The main event is Aðfangadagskvöld or Christmas Eve, when people meet for a Yule meal and exchange gifts. However, on the 13 days before December 24 the Yule lads or jólasveinar come into the towns from the mountains to give children that have behaved well small gifts. These they leave in shoes that have been placed near the window or on the window sill during the thirteen nights before Christmas Eve. Every night, a different Yule lad comes to visit, leaving either small gifts for well-behaved children, or a rotten potato if the child was naughty.

The Yule Lads, jólasveinarnir or jólasveinar, are figures from Icelandic folkore who in modern times have taken on the role of an Icelandic version of Santa Claus. There are thirteen jólasveinar. Originally, they were portrayed as mischievous pranksters who would steal from or harass the rural population, but in modern times they have been taking on a more benevolent role comparable to that of Santa Claus. They either wear late medieval Icelandic clothing or Santa Claus costumes. The jólasveinar are traditionally said to be the sons of the mountain-dwelling trolls Grýla and Leppalúði, and are often depicted with the Jólakötturinn or Yule cat.

The jólasveinar have descriptive names conveying their mode of operation and each day, a new lad arrives:

December 12 Stekkjarstaur (‘Sheep-Cote Clod’), harasses sheep but is impaired by his stiff peg-legs; leaves Dec.25

December 13 Giljagaur (‘Gully Gawk’), hides in gullies, waiting for an opportunity to sneak into the cowshed and steal some milk; leaves Dec. 26

December 14 Stúfur (‘Stubby’), unusually short, steals pans to eat the crust left on them; leaves Dec. 27

December 15 Þvörusleikir (‘Spoon-licker’), steals Þvörur (a type of wooden spoon – þvara- with a long handle) to lick them, is extremely thin due to malnutrition; leaves Dec. 28

December 16 Pottaskefill (‘Pot-scraper’), steals leftovers from pots; leaves Dec. 29

December 17 Askasleikir (‘Bowl-licker’), hides under beds waiting for someone to put down their ‘askur‘ (a wooden bowl with a lid), which he then steals; leaves Dec. 30

December 18 Hurðaskellir (‘door-slammer’), likes to slam doors, especially at night; leaves Dec. 31

December 19 Skyrgámur (‘Skyr-gobbler’), loves skyr (an Icelandic cultured dairy product which has the consistency of strained yoghurt, but a much milder taste); leaves Jan. 1

December 20 Bjúgnakrækir (‘sausage-swiper’), hides in the rafters and snatches sausages that were being smoked; leaves Jan. 2

December 21 Gluggagægir (‘window-peeper’), a voyeur who would look through windows in search of things to steal; leaves Jan. 3

December 22 Gáttaþefur (‘doorway-sniffer’), has an abnormally large nose and an acute sense of smell which he uses to locate laufabrauð (leaf-bread, an Icelandic specialty); leaves Jan. 4

December 23 Ketkrókur (‘meat-hook’), uses a meat hook to steal meat; leaves Jan. 5

December 24 Kertasníkir (‘candle-stealer’), follows children in order to steal their candles (which in olden days were made of tallow and thus edible); leaves Jan. 6

The Yule lads are often associated with the Jólakötturinn or Jólaköttur, or Yule Cat, a monster from Icelandic folklore, which is a huge and vicious cat said to lurk about the snowy countryside during Christmas time and eat people who have not received any new clothes to wear before Christmas Eve. The Yule Cat is the pet of the giantess Grýla and her sons, the Yule Lads. In former times, the threat of being eaten by the Yule Cat was used by farmers as an incentive for their workers to finish processing the autumn wool before Christmas. Those who participated in the work would get new clothes as a reward, but those who did not would get nothing and would therefore be preyed upon by the cat. The cat has alternatively been interpreted as merely eating away the food of those without new clothes during Christmas feasts. The tradition has its origin in the 19th century.

On January 6, Icelanders celebrate Þrettándinn (the thirteenth of jól), the last day of Christmas. It is celebrated with elf bonfires and elf dances. Families come together to have dinner and light fireworks. People also go into a corner of their houses and shout out the following folklore poem to drive out evil spirits and invite good spirits and elves:

- Komi þeir sem koma vilja (those come who want)

- Fari þeir sem fara vilja (those go who want)

- Mér og mínum að meinalausu (neither hurting myself nor my family)

Another Icelandic jól custom is the preparation of laufabrauð or ‘Leaf-bread’, which a kind of very thin pancake with a diameter of about 15 to 20 cm (6 to 8 inches), which is decorated with leaf-like, geometric patterns and fried briefly in hot fat or oil. Here is a video showing how it is made: https://youtu.be/OCeUnjax-7w

Here is a recipe for Laufabrauð (‘leaf bread’): http://jol.ismennt.is/english/laufabraud-joe.htm

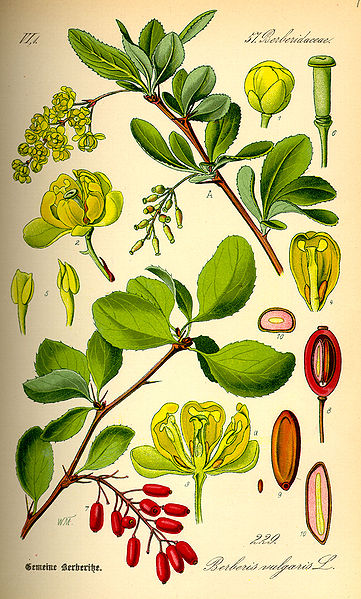

Focus on culture: Zereshk or barberries (Iran)

Today’s blog post is taking us to the Near East, and here in particular to Iran, and focuses on a particularity of the cuisine there, namely the berries called zereshk (زرشک) or barberries, as they are known in English.

Zereshk are the dried fruit of the Berberis shrub (Berberis integerrima ‘Bidaneh’), which is widely cultivated in Iran and can reach a height of up to 4 m. The plant is mildly poisonous except for its berries and seeds. The berries are very sour and have a tart flavor, and taste a bit like cranberries. They are rich in vitamin C and are used both for cooking and jam-making. A traditional dish in Iran is زرشک پلو (zereshk polow) or barberry rice, a dish of rice (pilaf) with spices, e.g. saffron, and zereshk-berries mixed into it. Other zereshk products include juice and zereshk fruit rolls.

Iran is the largest producer of zereshk, and zereshk and saffron are often produced on the same land and the harvest is at the same time. A garden of zereshk-shrubs is called zereshkestan ( زرشکستان) . The South Khorasan province in Iran is the main area of zereshk, and also of saffron, production in the world, especially the area around Birjand and Qaen.

Even though the barberry shrub is native to Central and Southern Europe, barberries are no longer widely known or used in Europe since the Berberis vulgaris (European barberry) is an alternate host species of the wheat rust fungus (Puccinia graminis), a grass-infecting rust fungus that is a serious fungal disease of wheat and related grains. For this reason, cultivation of barberries is prohibited in many places, e.g. in parts of Canada and the Unites States.