Scroll down for the English text!!

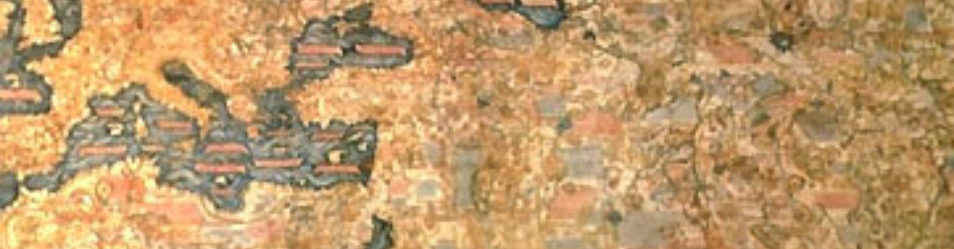

¿Dónde están?/Where are they? Anon. Chile, early 1980s

Photographer, Martin Melaugh (all images © Roberta Bacic), via http://www.latin-american.cam.ac.uk/events/arpilleras-dialogantes/arpillera-conversations

Esta semana, nuestro viaje nos lleva a Sudamérica, más precisamente a Chile, y a una forma distintiva de arte popular de este país – las arpilleras.

Arpilleras son tapices o imágenes textiles multicolores hechas con retales distintas que cuentan una historia y las experiencias de la vida cotidiana del pueblo. Son documentos históricos, mensajes de protesta y una forma del arte popular y del patriomonio al mismo tiempo. Tienen su origen en la dictatura militar de Augusto Pinochet Ugarte en Chile (1973-1990), durante la cual servían a documentar, a expresar y a denunciar la opresión y los crimenes del régimen porque todas otras formas de expresión libre normales eran prohibidas.

Las arpilleras chilenas fueron hechas por arpilleristas, grupas de mujeres cuyos maridos y/o hijos eran entre los víctimas del régimen, los así llamados ‘desaparecidos’ o ‘detenidos’. Fueron hechas en talleres organizados por una comisión de la Iglesia Católica chilena y entonces distribuídas en secreto al extranjero por la Vicaria de la Solidaridad, un grupo de derechos humanos de la iglesia católica de Santiago. El gobierno chileno consideraba las arpilleras traicioneras y prohibía su venta o exposición en el país, y por eso las primeras tapices fueron pasadas de contrabando al extranjero en bolsas diplomáticas. El régimen también confiscaba todos los paquetes, bolsas o maletas en los que sospecharon arpilleras. Por esta razón y para proteger a las mujeres, los tapices generalmente eran sin firmar. A menudo las ganancias de su venta en el entranjero eran los únicos ingresos de las arpilleristas porque a los parientes de detenidos o desaparecidos prohibieron hacer la mayoría de los trabajos.

Las raíces de las arpilleras datan de la época de los años 60 cuando una industria casera se desarrolló que producía bordados decorativos con escenas de la vida doméstica y rural con lana y hilos coloridos. Sin embargo, después del golpe militar en 1973, había escasez de lana y como consecuencia las arpilleristas empezaban a utilizar retales de paños por sus tapices. Las mujeres se reunían en pequeños talleres de un sólo cuarto en las afueras de Santiago cada semana para trabajar juntas. Cada taller tenía más o menos 20 miembros y a cada arpillerista se le permitió hacer sólo una arpillera cada semana, a menos que su necesidad de dinero era tan grande que el grupo decidió que podía hacer dos. El grupo también determinó el tema de las arpilleras cada semana. Cada arpillera era el trabajo de una mujer individual que desarrolló el diseño en el taller y luego lo cosió en casa.

Había algunas reglas respecto a los temas y a lo que podía ser mostrado en los tapices o no: por ejemplo, escenas de tortura u otros temas abiertamente políticos eran prohibidos, tanto como otras imágenes fuertes que puedan provocar el gobierno a detener a las mujeres. Solo eran permitidos eslóganes y palabras que también aparecían en la vida cotidiana, como sobre pancartas de manifestantes. Temas corrientes y comunes de las arpilleras son escenas de la vida rural y cotidiana, generalmente con los Andes en el fondo como testimonio e indicio de que las cuentas representadas tenían lugar en Chile, y casas, árboles y figuras humanas – generalmente tridimensionales con piezas como cabezas, brazos, etc. que resaltan de la superficie plana. Imágenes recurrentes incluyen ollas comunes (grandes calderos negros sobre un fuego) que la Iglesia chilena suministraba, los talleres de arpilleras mismos, las bombas de agua comunales y panaderías y lavanderías cooperativas que eran organizadas para ayudar a los pobres. Representaciones más políticas incluían grupos de manifestantes que llevaban pancartas y distribuían folletos políticos – ambos actos ilegales – , la policía militar con uniformes oscuros o puertas de fábricas y hospitales con una X sobre ellas, lo que significaba que eran cerradas a las familias de los desaparecidos o detenidos. Otros temas frecuentes eran niños que rebuscaban y coleccionaban cartones para venderlos, que lavaban coches o hacían cola delante de los hospitales o para recibir leche, o líneas eléctricas que la gente conectaba con las líneas eléctricas principales durante la noche para robar electricidad después de que el gobierno cerró su suministro de electricidad. Otros materiales, como por ejemplo frijoles secos, piezas de plástico, de papel, metal o de madera, fueron también cosidos o pegados a la superficie de las arpilleras.

Sin embargo, no todas las arpilleras mostraban escenas políticas y denunciantes: Algunas retratan una vida ‘idealizada’ como las mujeres la habrían deseado, con niños alegres, un paisaje pacífico, mercados florecientes y un buen Sistema de asistencia sanitaria, etc. – en breves palabras, retratos que expresaron el deseo y la esperanza de un futuro mejor. Por otro lado, había también talleres de arpilleras sancionados por el gobierno en los que mujeres fieles a la dictatura cosían tapices de propaganda, con temas alegres que retrataron a Chile como un país próspero con un gobierno benévolo. Con el tiempo, el arte de las arpilleras fue también adoptado por la gente en otros países latinoamericanos, especialmente en Perú, Nicaragua y Colombia, y sus tapices casi siempre retratan una vida feliz.

English text:

Today’s blog post is taking us to South America and Chile and to an art form that originated in this country, namely the Arpilleras, patchwork tapestries that were made by groups of women, the arpilleristas, during the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte (1973-1990) in Chile. The name arpillera derives from the Spanish word for ‘burlap’ (=arpillera), a type of sackcloth onto which the designs were sewn.

Arpilleras are small figurative patchwork tapestries made from scraps of fabric, which tell a story and the experiences of daily life of the makers and typically depict images of hardship, violence and of oppressive living conditions and human rights abuses during the regime. They are historical records, protest messages and a form of folk art and heritage at the same time. They have their origin in the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet Ugarte in Chile (1973-1990), during which all normal means of free speech and of free expression were prohibited and so they served as an outlet to document, denounce and express the oppression and crimes of the regime.

The Chilean arpilleras were made by the arpilleristas, groups of women whose husbands and sons were among the desaparecidos, literally ‘those who have disappeared’, and the detained. They were made in workshops organized by a commission of the Chilean Catholic Church and then distributed abroad in secret by the Vicaria de la Solidaridad, the Vicarate of Solidarity, a human rights group of the Catholic church of Santiago. The Chilean government considered the arpilleras as traitorous and prohibited their sale and exhibition in the country. Therefore, the first tapestries had to be smuggled out of the country in diplomatic pouches. The regime also confiscated all packages, bags and suitcases in which they suspected arpilleras. For this reason and to protect the women, the tapestries were usually not signed. The proceeds from their sale abroad was often the only source of income of the arpilleristas because the relatives of the detained and disappeared were barred from most jobs.

The roots of this folk art practice date back to the 1960s when a home-based industry developed which produced decorative embroidered wall hangings with scenes of domestic and rural life made from wool and colourful threads. However, after the military coup in 1973, there was a scarcity of wool and so the arpilleristas started using fabric scraps for their tapestries. The women met in small one-room workshops in the outskirts of Santiago each week to work together. Each workshop had about 20 members and each arpillerista was only allowed to make one tapestry each week, unless she was so needy that the group allowed her to make two. The group also decided a topic for the tapestries to be made that week, but each arpillera was nevertheless the work and design of an individual woman who developed the design in the workshop and then sewed the tapestry at home.

There were several rules about subject matter and about what could be shown in the tapestries and what not: for example, scenes of torture and other overtly political topics were prohibited, as well as other strong images which could provoke the government to detain the women. Only slogans and phrases which also appeared in daily life, like on banners of demonstrators, could be included. Recurring and common subjects of the arpilleras are scenes of rural and daily life, usually with the Andes mountains, los Andes, in the background as a testimony and an indication that the stories represented in the tapestries took place in Chile, as well as trees, houses and human figures – generally three-dimensional with pieces like arms, heads, etc. projecting from the flat surface. Other recurring imagery includes the so-called ‘common pots’, or ollas comunes (big black cauldrons on a fire), i.e. soup-kitchens which the Catholic church provided, the arpillera workshops themselves, communal water pumps and co-operative bakeries and laundries, which were organized to help the poor. More political images include groups of demontrators who carried banners and distributed political pamphlets – both of which were illegal actions – , the military police with their dark uniforms or doors of factories and hospitals with an X on them, which signalled that they were barred for the families of the desaparecidos, ‘those who have disappeared’, and of the detained. Further recurring subjects are children who searched for and collected cardboards to sell, who washed cars or were queuing in front of hospitals or to receive some milk, as well as electrical lines which people connected to the main power lines at night to steal electricity after the government shut down their own power supply. Other materials, like for example dried beans (frijoles secos), pieces of plastic, metal or wood, were also sewn or glued to the surface of the arpilleras.

However, not all of these patchwork tapestries showed political or denouncing subject matter: Some painted the picture of an ‘idealized’ life which the women would have wished to have, with happy children, peaceful landscapes, flourishing markets and a good health care system, etc. – in short, images which expressed the wish and hope for a better future. On the other hand, there were also workshops for government-sanctioned arpilleras, in which women loyal to the dictatorship sewed propaganda tapestries, with cheerful subject matter which portrayed Chile as a prosperous country with a benevolent government. Over time, the folk art of making arpilleras was taken over by people in other Latin American countries, especially Peru, Nicaragua and Colombia, and their tapestries almost always show scenes of a happy life.

Further reading:

What is an Arpillera? http://benton.uconn.edu/exhibitions/arpilleria/what-is-an-arpillera/

Telling the story https://www.brandeis.edu/ethics/events/past/tellingthestory/agosin.html