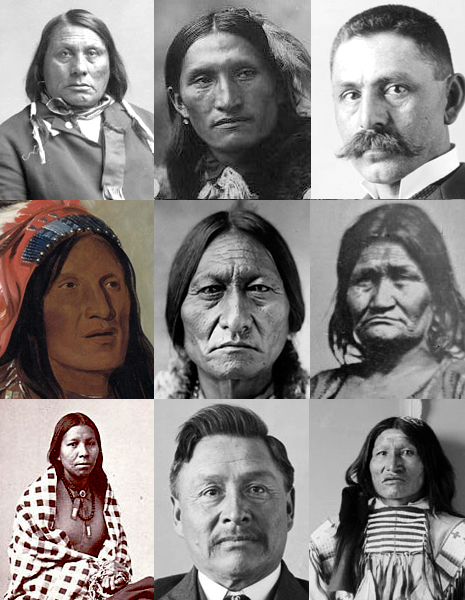

Author: John C.H. Grabill, digital restoration by Michel Vuijlsteke via Wikipedia Commons

Oglala girl in front of a tipi

Today’s blog post will take us to two First Nations in the US and Canada, and will be about the names of the months in Lakota or Lakȟótiyapi (also known as Sioux), a Siouan language spoken by the Lakota nation (Lakȟóta) in North and South Dakota in the United States, and tell the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) legend of the origin of the dreamcatcher.

The Lakȟótiyapi word ‘wi’ means ‘moon’ or ‘month’, and ‘wiyawapi’ means ‘a months count or calendar’.

January wiocokanyan (lit. ‘the middle moon’) or wiotehika (‘the hard moon’)

February cannapopa wi (‘the moon when trees crack because of the cold’) or tiyoheyunka wi (‘moon where the frost is settling on the inside wall of the house or tent’) or wicata wi (‘the raccoon moon’)

March ištawicayazan wi (‘the moon of prevailing sore eyes’) or ištawicaniyan wi (‘the moon of sore eyes’) or šiyo ištohcapi wi (šiyo ‘grouse, prairie hen’; ‘moon of the grouse and of sore eyes’)

April wihakakta cèpapi (‘wihakakta’ means ‘the fifth child’, so called because it was usually the last child or the youngest; ‘cepa’ means fat; the youngest wife had to crack the bones and people would get fat on the marrow)

May canwapto wi (‘moon in which the leaves are green’ from ‘canwape’ [from can ‘tree’ + ape ‘leaf’] meaning ‘leaves’ or ‘small branches’) or wójupi wi (‘the moon of planting’)

June tínpsinla itkahca wi (‘the moon when the seedpods of the wild turnip blossom’) or wípazuka wašte (‘wípazukan’, a red berry growing in small bunches in June; ‘wašte’ meaning ‘good, pretty’; therefore ‘moon of the good red wípazukan berries’)

July canpasapa wi (‘the moon when the choke-cherries are black’) or wiocokanyan (‘the middle moon’)

August wasuton wi (‘the harvest moon’)

September canwape gi wi (‘moon in which leaves turn brown’)

October canwape kasna wi (‘the moon in which the wind shakes off leaves’)

November takiyuha (‘the moon when deer copulate’) or waniyetu wi (‘the winter moon’)

December tahecapšun wi (‘the moon in which deer shed their horns) or wanicokan wi (‘the mid-winter moon’)

What is quite interesting is that the word ‘wiocokanyan’, meaning the ‘middle moon’, can refer to both January and July.

Author: Arturo de Frias Marques via Wikipedia Commons

American bison ‘Tatanka’

And some Lakhotiya words:

Tatanka the male buffalo

Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka – lit. ‘the sacred’ or ‘the divine’, usually translated as ‘the Great Mystery’; the term refers to the power or sacredness that resides in everything, resembling pantheistic or animistic beliefs. Every creature and object has some aspects that are considered wakȟáŋ (“holy”).

Author: Media123 via Wikipedia Commons

iháŋbla gmunka (iháŋbla ‘to dream, to have visions’, gmunka ‘to trap’) ‘dreamcatcher’, a handmade object made from a willow hoop and sinew or cordage made from plants, which is woven around the hoop to form a net or web. The dreamcatcher is decorated with sacred items such as beads and feathers which all have a symbolic meaning. Dreamcatchers actually have their origins in the Ojibwe nation, where they are called bawaajige nagwaagan meaning “dream snare” or asabikeshiinh (the inanimate form of the word for ‘spider’), but have been adopted by Native Americans of different nations in the Pan-Indian Movement of the 1960’s and 70’s as a symbol of unity and identification with the First Nations. However, other groups see dreamcatchers as offensively misappropriated and misused by non-Natives. The circular shape represents how giizis (Ojibwe, meaning ‘the sun, moon, month’) travels each day across the sky.

There is an ancient Ojibwe legend about the origin of the dreamcatcher: the Spider Woman, known as Asibikaashi, took care of the children and the people on the land. Eventually, when the Ojibwe Nation spread all over North America, it became difficult for Asibikaashi to reach all the children. So the mothers and grandmothers would weave magical webs for the children from willow hoops in the form of dreamcatchers which would filter out all bad dreams and only allow good thoughts to enter the mind, making the bad dreams disappear once the sun rises.

Finally a booktip for those of you who are interested in Native American spirituality and culture in general and the Lakota Nation in particular:

‘The Lakota Way – Stories and Lessons for Living’ by Joseph M. Marshall III

If you live in the UK: http://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/0142196096

If you live in the US: http://amzn.com/0142196096